100 Greatest Red Sox >> #33 Curt Schilling

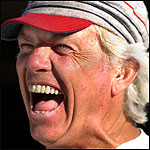

Curt Schilling, SP, #38 (2004-current)

44 Wins - 21 Losses, 9 Saves, 524 IP, 473 Ks, 85 BBs, 3.97 ERA With the exception of Barry Bonds there really isn't a baseball player active today with a more polarising effect on the public and indeed the sports media than Curt Schilling.

With the exception of Barry Bonds there really isn't a baseball player active today with a more polarising effect on the public and indeed the sports media than Curt Schilling.

He is an unusual entity, a professional athlete who is more than happy to talk with the media, so much so that he runs his own blog. This 'ease' with which he approaches his media encounters leads some fans and professional writers to find fault in how Schilling runs his life, both on and off the field.

Strip all that away though, and what do you have? Schilling is a potential hall of fame candidate who has shone particularly bright in the postseason. After the regular season Schilling is 8-2 with a 2.06 ERA and 104 strikeouts in 109.1 Innings. Whatever about the scintillating statistics, Schillling is a two-time World Series winner and furthermore does incredible things in terms of his charity works outside the game.

All the childish barbs the Dan Shaughnessy's of this world throw at Schilling can't take his brilliant career away from him.

Born November 14, 1966, Curt Schilling is just the ninth Major League player to have hailed from Alaska. Curt spent his youth in Phoenix, Arizona and attended Shadow Mountain High School before attending Yavapai College in Prescott, Arizona. He was a winner at an early age, helping lead Yavapai College to the 1985 Junior College World Series. Amazingly, Schilling began his professional career in the Boston Red Sox farm system but was traded to the Baltimore Orioles in 1988 for Mike Boddicker. His major league debut was with the Orioles (1988-1990), he spent one year with the Houston Astros (1991), and then spent more than eight exciting seasons with the Philadelphia Phillies (1992-2000).

Schilling was one of the major factors in the Phillies' great pennant run in 1993. In that year, Schilling went 16-7 with a 4.02 ERA and 186 strikeouts. Schilling then led the Phillies to an upset against the two-time defending National League champion Atlanta Braves in the National League Championship Series. Schilling's 1.69 ERA and 19 strikeouts earned him the 1993 NLCS Most Valuable Player Award. The Phillies went on to lose to the defending World Champion Toronto Blue Jays in the World Series. They slipped into relative mediocrity in the years after that, despite Schilling being the ace of the staff. Disappointed that the Phillies front office was not doing enough to field a competitive team Schilling eventually asked for a trade, and got his wish in 2000 when he was sent to the Arizona Diamondbacks. Curt Schilling's amazing career took on greater impetus when he moved to Arizona. With the D-Backs, he went a spectacular 22-6 with a 2.98 ERA in 2001 and went 4-0 with a 1.12 ERA in the playoffs. In the 2001 World Series the Diamondbacks won one of the most famous World Series finalés ever beating the New York Yankees in 7 games. Many say that game was the beginning of the end for that particular Yankee team. Schilling shared the 2001 World Series MVP Award star with teammate Randy Johnson. In 2002 Schilling went an excellent 23-7 with a 3.23 ERA. Both years he finished second in the Cy Young Award voting to Johnson.

Curt Schilling's amazing career took on greater impetus when he moved to Arizona. With the D-Backs, he went a spectacular 22-6 with a 2.98 ERA in 2001 and went 4-0 with a 1.12 ERA in the playoffs. In the 2001 World Series the Diamondbacks won one of the most famous World Series finalés ever beating the New York Yankees in 7 games. Many say that game was the beginning of the end for that particular Yankee team. Schilling shared the 2001 World Series MVP Award star with teammate Randy Johnson. In 2002 Schilling went an excellent 23-7 with a 3.23 ERA. Both years he finished second in the Cy Young Award voting to Johnson.

2003 was a rough year for the Boston Red Sox. Although the team made the playoffs, the traumatic loss to the Yankees in the ALCS combined with public displeasure with the bullpen led to Theo Epstein and the Sox front office determinedly attacking the free agent market in advance of the 2004 season. They signed Keith Foulke to be the teams closer and then made an even bigger splash in November 2003 by trading for Curt Schilling. Curt would join Derek Lowe, Pedro Martinez and Tim Wakefield to form on of the more eclectic and talented pitching rotations ever assembled.

Straight off the bat Schilling endeared himself to the Sox faithful by appearing in interviews wearing a 'Yankee hater' baseball cap and promising to lead his new team past their rivals from the Bronx. This was no idle promise coming from a man who had already vanquished the Yankees in the 2001 World Series.

Schilling backed his promises up on the field, in style. For 2004, his first season with the Red Sox, Curt posted a sparkling 21-6 record, becoming the first Boston pitcher to win 20 or more games in his first season with the club since Dennis Eckersley in 1978.

The Sox super season looked in serious jeopardy during the ALCS against the Yankees. The Bronx bombers were 3-0 up and no Major League team had ever come back from such a deficit. That's when Kevin Millar made his infamous quote “Don’t Let Us Win Tonight”, referring to how the Red Sox had excellent starting pitching lined up for the next few nights. Sure enough, Boston started to crawl back into the ALCS on the back of great pitching and clutch hitting.  On October 19, 2004 Schilling won Game 6 of the 2004 American League Championship Series against the New York Yankees. Amazingly he won this game playing on an injured ankle, an injury so bad that by the end of his performance that day his white sock was soaked with blood.

On October 19, 2004 Schilling won Game 6 of the 2004 American League Championship Series against the New York Yankees. Amazingly he won this game playing on an injured ankle, an injury so bad that by the end of his performance that day his white sock was soaked with blood.

This bloody sock would go on to become one of the most vivid symbols in recent baseball history.

That dramatic victory forced a Game 7, meaning the Red Sox were the first team in post-season Major League Baseball history to come back from a three-games-to-none deficit. The Red Sox would go on to win Game 7 of the ALCS and make their first World Series appearance since 1986. They had done it, they had come all the way back against their legendary rivals and now stood on the verge of their first World Series win since 1918.

Schilling pitched (and won) Game 2 of the 2004 World Series for the Red Sox against the St. Louis Cardinals. He actually had to have the tendon in his right ankle stabilized but the tendon sheath was torn and, as in Game 6 of the ALCS, Schilling's sock was soaked with blood from the sutures used in this medical procedure. Schilling amazingly still managed to pitch seven strong innings, giving up one run on four hits, whilst striking out four. That was all Boston needed from him and they swept the hapless Cardinals in four games, bringing home the championship to Boston for the first time since 1918.

Schilling's place in baseball history was secured and his second bloody sock was placed in the Baseball Hall of Fame after the World Series. Schilling was once again runner-up in Cy Young voting in 2004, this time his Randy Johnson was Minnesota Twins hurler Johan Santana, who received all 28 first-place votes. Schilling received 27 of the 28 second-place votes.

The drama of 2004 came at a steep price. Schilling's ankle injury had an immense effect on his pitching performance in 2005. He began the year on the disabled list, and when he finally returned he did so to log an up and down season with constant questions being asked of his ability to overcome the injury. 2006 brought a welcome return to the Schilling of old, and Curt managed a tidy 15-7 record with 198 K's and a very respectable 3.97 era.

Schilling opened 2007 with the announcement that he will pitch in 2008. and he has managed to start the season in such a fashion that no one is accusing him of being distracted by contract talks. He has pitched, at times, as the Red Sox ace and figures to lead a potentially fantastic staff into the 2007 playoffs with the Sox currently holding a double digit lead over all rivals in the AL East.

Schilling is a fascinating character. A thoughtful, often eloquent man who is not afraid to speak his mind he draws a host of emotions from a wide variety of people. Two things though, stand out. Schilling's tireless work with the various charities he strives to improve has been a constant in his career. He clearly cares, deeply, about those charities.

Secondly, the man delivers on his promises. He promised Boston a return to former glory, and he has been a major part in delivering on said promise. He will always be a major part of the greatest Old Town team of all, the 2004 Boston Red Sox.

This Top 100 Red Sox of all time profile was written by Cormac Eklof @ ''I didn't know there was baseball in Ireland?!''